Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Golden Age: A Literature That Defined a Nation

- American Literature Today: A Fragmented Landscape

- The Role of Technology: A Double-Edged Sword

- The Decline of the Public Intellectual

- The Education Crisis: Who’s Reading the Classics?

- Is There Still Hope?

- Conclusion

Introduction

American literature is a curious beast. It has been both a mirror and a magnifying glass, reflecting the nation’s spirit while also enlarging its flaws and contradictions. It has produced giants who shook the literary world, set trends that rippled globally, and sparked debates that still smolder. Yet today, a cloud hangs over American literature. Readers are dwindling, publishing houses are consolidating, and critics are asking uncomfortable questions: Has American literature lost its way? Are we witnessing the end of an era?

Of course, every generation proclaims its own literary apocalypse. In the 1920s, people lamented that the Jazz Age was ruining serious writing. In the 1950s, critics fretted about the rise of pulp novels. Today’s worries may echo those fears, but they also stem from unique cultural, technological, and economic forces. This article provides a comprehensive examination of the past glories, current dilemmas, and future prospects of American literature. It might not provide comforting answers, but it will definitely ask the right questions.

The Golden Age: A Literature That Defined a Nation

There was a time when American literature not only reflected the culture, but also shaped it. The 19th century saw American writers striving to break free from European influences and craft a distinctly American voice. Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper were among the first to gain international acclaim, but it was writers like Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, and Walt Whitman who carved out a literary identity that felt unmistakably American.

Whitman’s Leaves of Grass wasn’t just a book; it was a declaration of independence for American poetry. Melville’s Moby-Dick wrestled with existential questions as vast as the sea itself. Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter dug into the moral hypocrisies of Puritan America. Together, they helped forge a literary tradition centered on themes like individualism, morality, and the search for identity.

Then came the 20th century, the true golden age. The American literary scene exploded with voices that were bold, experimental, and unflinching. F. Scott Fitzgerald captured the disillusionment of the Roaring Twenties in The Great Gatsby, while Ernest Hemingway’s sparse, stripped-down prose became a blueprint for generations of writers. William Faulkner redefined the American South in labyrinthine novels like The Sound and the Fury. Later, Toni Morrison would force readers to confront America’s racial traumas with unforgettable works such as Beloved.

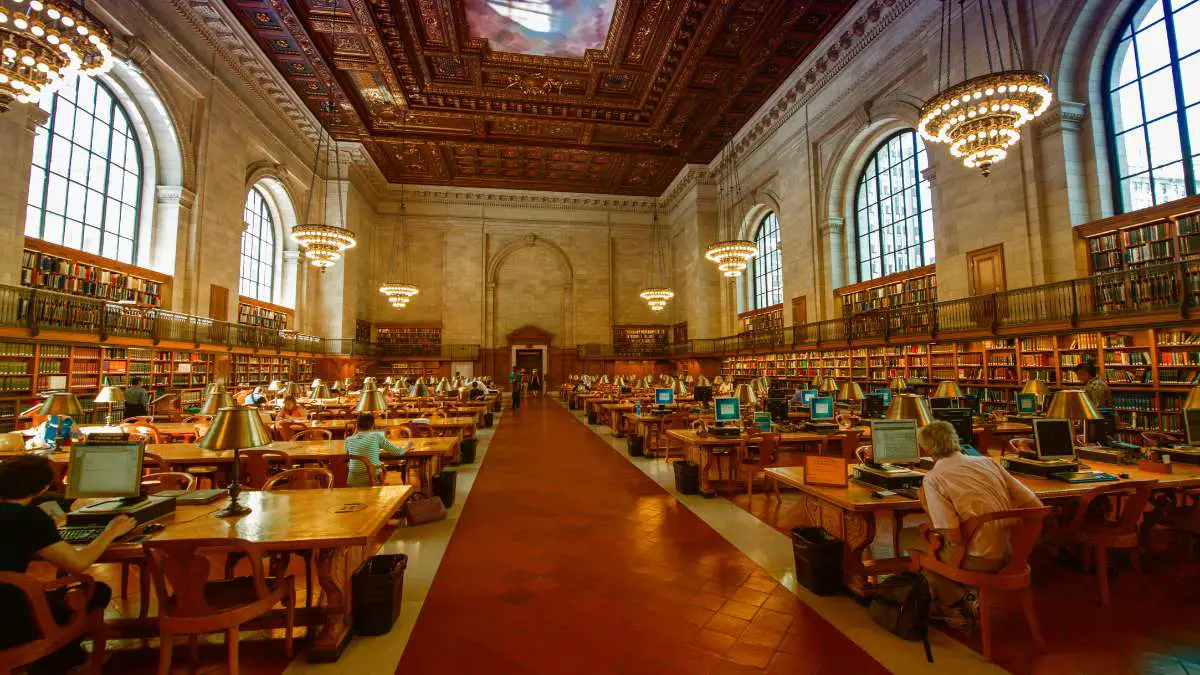

During this era, literature wasn’t just a pastime for academics and bohemians. It was part of the national conversation. Novels routinely topped bestseller lists while also being dissected in college classrooms. Writers were public intellectuals, whose opinions were sought on politics, culture, and the state of the human soul.

American Literature Today: A Fragmented Landscape

Fast-forward to the 21st century, and the landscape looks vastly different. Today’s literary scene is fragmented, niche-driven, and often drowned out by louder forms of entertainment. Netflix binges, TikTok videos, and video games compete for the same leisure hours once reserved for novels. And for many, literature simply can’t compete.

The publishing industry itself reflects this fragmentation. While giants like Penguin Random House and HarperCollins still dominate, there’s been an explosion of indie presses, hybrid publishers, and self-publishing platforms. These alternative routes have opened doors for marginalized voices that traditional publishers long ignored, but they’ve also made it harder for any single book or author to command national attention.

One could argue that this democratization is a good thing. More voices, more diversity, more stories. What’s not to love? And indeed, today’s American literature is richer and more varied than ever. Writers like Viet Thanh Nguyen, Jesmyn Ward, Colson Whitehead, and Tommy Orange are producing works that grapple with race, history, and identity with extraordinary nuance.

But there’s a flip side. The sheer glut of books means that literary culture feels scattered. Instead of a few major authors dominating public discourse, we now have countless micro-literatures operating in silos. One group obsesses over autofiction; another champions experimental fiction; yet another devours YA dystopias. The notion of a shared national literary canon is fast becoming a relic.

The Role of Technology: A Double-Edged Sword

Technology has always had a complicated relationship with literature. In the 20th century, radio and television were seen as threats to the novel. Today, it’s the internet, and social media in particular, that has critics sounding alarm bells.

Platforms like TikTok and Instagram have warped how books are marketed and consumed. BookTok, for instance, has become a powerful engine for book sales, particularly in the young adult and fantasy genres. Some argue that this is simply a new way to encourage people to read. Others fret that it reduces literature to a series of viral trends and aestheticized “shelfies.”

Then there’s the question of attention spans. Studies show that sustained reading has been declining for years. According to a 2021 Pew Research Center survey, approximately 23% of American adults reported not reading any books in the previous year. However, this figure encompasses all types of books, not just literary fiction. Social media algorithms aren’t designed for the kind of deep, immersive concentration that serious literature requires. They thrive on quick dopamine hits, not slow-burn narratives.

And yet, technology isn’t purely an enemy. E-books and audiobooks have made literature more accessible than ever. Online writing communities have given rise to a new generation of authors, many of whom started on fan-fiction forums before landing major publishing deals. Writers like E.L. James (Fifty Shades of Grey) and Andy Weir (The Martian) owe their careers to the digital age.

The Decline of the Public Intellectual

One of the most glaring differences between American literature’s past and present is the diminished role of the public intellectual. Once upon a time, authors like James Baldwin, Susan Sontag, and Norman Mailer were household names, not just for their novels but for their essays and public debates. They shaped the national conversation on a wide range of issues, from civil rights to foreign policy.

Today, it’s hard to name a single novelist with that kind of cultural clout. The closest equivalents—perhaps Ta-Nehisi Coates or Roxane Gay—are as well known for their social media presence and nonfiction writing as for their fiction.

Part of this decline stems from changes in media itself. The decline of the long-form magazine essay, the contraction of newspaper book sections, and the rise of clickbait journalism have all made it more challenging for serious literary thinkers to gain traction. It’s also a result of a more polarized political climate, in which authors are often expected to take clear, activist stances, sometimes at the expense of literary nuance.

The Education Crisis: Who’s Reading the Classics?

The decline of American literature is also tied to changes in education. Once, high school and college syllabi were packed with canonical American works: The Catcher in the Rye, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Grapes of Wrath. Today, those same works are frequently challenged or removed altogether, either because they are deemed too offensive or too dated.

There’s also been a broader devaluation of the humanities in education. STEM fields dominate funding and student enrollment, while English departments struggle to justify their existence. Many universities have reduced or eliminated literature courses.

This educational shift has ripple effects beyond the campus. If young people don’t grow up reading serious literature, they’re unlikely to develop the habit as adults. And if schools aren’t teaching students how to engage with complex narratives, we shouldn’t be surprised when the literary marketplace caters to simpler, more digestible fare.

Is There Still Hope?

Despite all these gloomy trends, it would be premature to write American literature’s obituary just yet. In fact, some might argue that it’s going through a necessary metamorphosis.

For one, the diversification of voices has led to some of the most exciting work in decades. Indigenous writers like Louise Erdrich and Tommy Orange, immigrant authors such as Jhumpa Lahiri and Yaa Gyasi, and queer authors like Ocean Vuong are all pushing the boundaries of American literature in profound ways.

Moreover, the very fragmentation of the literary world can be a strength. No longer tethered to a single, monolithic vision of American identity, literature today explores multiple Americas—rural and urban, conservative and progressive, privileged and marginalized.

And while the publishing industry may be a chaotic mess, it’s also more adaptable than it gets credit for. Independent presses like Graywolf, Coffee House, and New Directions consistently publish some of the most daring, inventive fiction out there. Online magazines and literary newsletters offer platforms for emerging voices, free from the constraints of corporate publishing.

Finally, readers themselves may yet surprise us. There’s a growing backlash against digital distraction, with movements like “slow reading” and “digital detox” gaining traction. Book clubs are thriving, particularly among millennials and Gen Z, who are rediscovering the communal joy of shared reading experiences.

Conclusion

So, is this the end of an era for American literature? Perhaps. But eras don’t simply end; they evolve. The old model—of a few towering authors dictating the national literary conversation—is indeed vanishing. In its place, we’re getting a messier, more diverse, and frankly more interesting literary world.

There’s no denying the challenges ahead. Publishing economics remain brutal, cultural attention spans are shrinking, and the role of the author as public intellectual has greatly diminished. Yet, literature has always been a shape-shifter, and American literature, in particular, thrives on reinvention.

The question isn’t whether American literature is dying. It’s what it’s transforming into, and who gets to decide what counts as literary greatness in this new era.