Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Expanding Role of AI in Editorial Tasks

- What Human Editors Still Do Best

- The Limits of AI Judgment

- Shifting Skills in a Hybrid Editorial Future

- Collaborative Editing: Human + AI

- Implications for Academic, Trade, and Independent Publishing

- Ethical and Legal Considerations

- The Editor as Curator and Cultural Steward

- Conclusion

Introduction

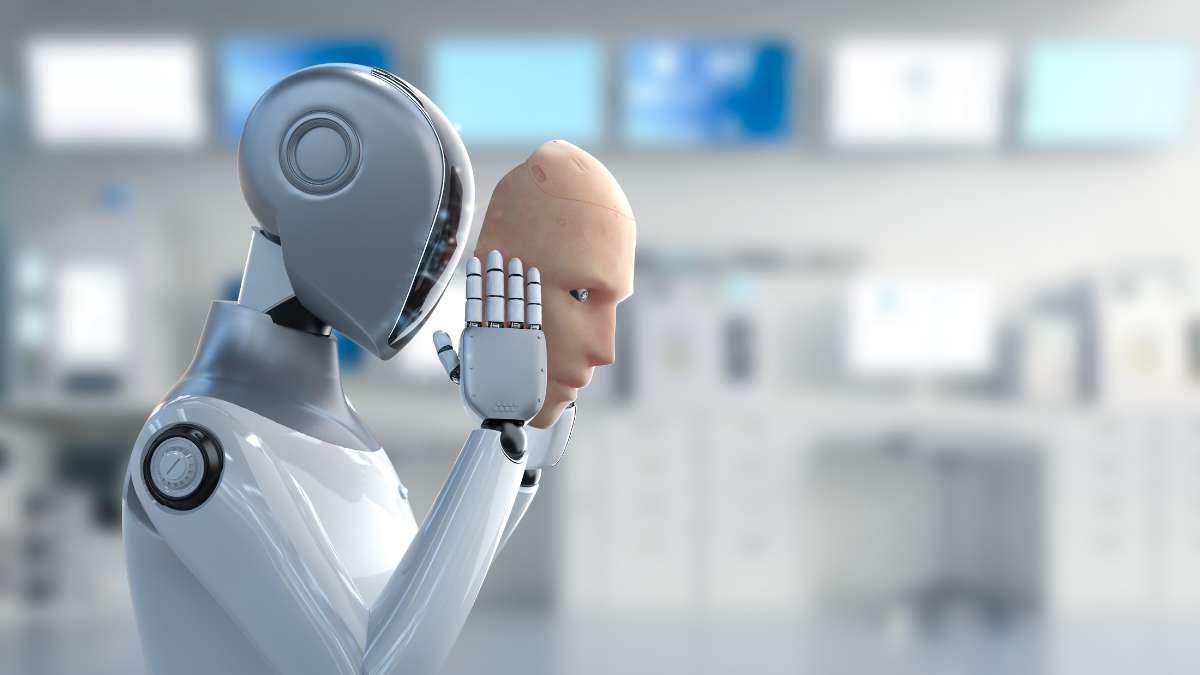

Artificial intelligence (AI) has already reshaped numerous aspects of modern publishing—automating repetitive tasks, assisting with metadata generation, and enhancing discoverability. But as tools like ChatGPT, Grammarly, and Claude evolve, a question has begun to ripple through editorial departments, boardrooms, and literary festivals alike: Will AI replace human editors?

This is not a new kind of question. It echoes past anxieties—about typesetters during the shift to digital printing, about bookstores when Amazon surged online, and more recently, about the fate of writers themselves. But editing is different. Editing is not just correction; it is interpretation, judgment, and vision. So when people wonder if AI will replace editors, they are not merely asking about job security. They are questioning the future of literary quality, cultural nuance, and the human voice in publishing.

This article explores the capabilities and limitations of AI in the context of editorial work and attempts to answer the intriguing question: Will AI replace human editors? We will examine the current tools available, how they are used, and where human editors still maintain a distinct advantage. Along the way, we’ll consider how the role of the editor may evolve—and why the conversation shouldn’t be framed around replacement, but rather, collaboration and transformation.

The Expanding Role of AI in Editorial Tasks

AI is already performing a range of editorial functions, from grammar correction and plagiarism detection to basic style adjustments and readability enhancements. Tools like Grammarly, ProWritingAid, and Microsoft Editor have made it easy to polish text quickly. More advanced platforms like ChatGPT and Jasper AI can rephrase paragraphs, suggest alternative headlines, and even summarize chapters. In publishing workflows, these tools are being used not just by editors but also by authors, proofreaders, and marketing teams.

For routine tasks—checking consistency in spelling, identifying passive constructions, and enforcing house styles—AI offers remarkable efficiency. Many publishers have already embedded these tools into their CMS or editorial pipelines, freeing up human editors to focus on more substantive aspects of the manuscript.

However, this kind of automation doesn’t involve editing in the traditional sense. It’s more akin to high-speed copyediting or linguistic triage. It enhances productivity, certainly, but doesn’t yet rise to the level of nuanced decision-making. AI can fix a sentence, but it doesn’t question the sentence’s necessity. It doesn’t ask, “Is this really what the author wants to say?” That deeper level of engagement remains a human domain.

What Human Editors Still Do Best

A seasoned editor does far more than clean up grammar. Developmental editors help shape the structure of books, identify weaknesses in argumentation, suggest new directions for a narrative, and even intervene when a manuscript loses clarity or momentum. Line editors focus on tone, pacing, and flow—qualities that cannot be easily quantified. A good editor acts as both the first audience and a critical friend.

There are several reasons why AI still struggles in these areas. For one, it lacks lived experience. A human editor brings cultural context, emotional intelligence, and institutional memory. They understand audience expectations, genre conventions, and social nuances in a way that AI cannot replicate, especially in multilingual or cross-cultural contexts.

Moreover, editing is often collaborative. Editors work closely with authors, negotiating meaning, tone, and sometimes even ideology. These relationships are built on trust, mutual respect, and shared goals. AI may assist in this process but does not participate in it as a peer.

Even more critically, editors serve a gatekeeping role in publishing, deciding which works are worthy of print. This involves taste, ethics, brand alignment, and even market foresight. While AI might generate market predictions, it lacks discernment and instinct, qualities central to the editorial profession.

The Limits of AI Judgment

There’s a persistent myth that AI is neutral and objective. In practice, AI models inherit the biases of their training data. This has led to awkward, and at times offensive, outputs—an obvious liability in a field like publishing where sensitivity to language, representation, and inclusivity is paramount.

Editors must constantly navigate complex terrain—avoiding harmful tropes, ensuring accurate representation, and managing potentially controversial content. These are not binary decisions. They involve ethical reasoning, social awareness, and careful listening. Current AI tools, even those equipped with content filters or alignment strategies, remain blunt instruments in this regard.

There’s also the problem of false confidence. AI can produce outputs that sound authoritative but are factually incorrect or contextually misleading. A human editor can sense when something feels “off”—an instinct honed over years of reading and refining. AI lacks that gut feeling. It will not pause and ask, “Wait, is this actually true?” unless specifically programmed to do so.

Shifting Skills in a Hybrid Editorial Future

Human editors are more likely to evolve rather than be replaced. Editorial roles are already expanding to include AI literacy—knowing how to use these tools effectively, where their outputs can be trusted, and where they should be challenged or ignored.

Editors who understand AI tools can speed up certain tasks, reduce fatigue, and redirect energy toward creative judgment. For instance, an editor might use an AI summary tool to process a dense academic manuscript more quickly before diving into substantive review. Or they might use natural language processing to scan for overused terms, allowing for more precise revisions.

In this sense, an editor’s skill set is shifting. Technical literacy, data awareness, and digital fluency are becoming as important as grammar and style. Future editors may spend as much time managing AI-generated content as they do line-editing it. Their value will lie in bridging machine output and human insight.

Collaborative Editing: Human + AI

The most promising future for publishing lies in human-AI collaboration. This is not just about making editing faster but deeper. AI can provide real-time feedback on readability, tone, and even emotional resonance. Editors can then interpret, challenge, or reframe that feedback within a larger vision for the work.

Imagine a scenario where AI suggests three ways to restructure a chapter for better pacing, but the editor chooses the one that aligns with the author’s intent. Or where AI flags a potential cultural insensitivity, and the editor consults with sensitivity readers to resolve the issue. These are not science-fiction scenarios; they are happening now in forward-looking publishing houses.

At the same time, this collaboration introduces new ethical questions. Who owns the final text? Who is accountable when AI makes a bad call? How transparent should the editorial process be when AI is involved? These questions are not trivial, and the answers will shape trust in the editorial process itself.

Implications for Academic, Trade, and Independent Publishing

The impact of AI on editing will differ across publishing sectors. AI may assist with citation checks, format compliance, or peer review coordination in academic publishing. But it won’t replace peer reviewers or editorial boards. In fact, the complexity and rigor of scholarly communication may make the human editor even more indispensable as a quality assurance layer.

Trade publishing depends heavily on voice, tone, and reader engagement, especially for fiction and general nonfiction. Here, AI may help in early drafts—cleaning prose or suggesting alternatives—but it won’t replace the editor’s role in curating style or identifying narrative arcs. The art of storytelling remains deeply human.

Given budget constraints, independent publishers and self-published authors may adopt AI more aggressively. These tools can help level the playing field, providing access to basic editorial functions that would otherwise be unaffordable. However, without careful oversight, the quality of published content may vary widely, raising new concerns about editorial standards in the digital marketplace.

Ethical and Legal Considerations

The use of AI in editing also raises legal and ethical issues. For instance, if an AI tool plagiarizes or reproduces copyrighted content in its suggestions, who is liable? Editors must now consider not just what a manuscript says but how it was produced—and by whom.

There’s also the matter of disclosure. Should authors be informed when AI is used to edit their work? Should readers? These are unresolved debates, and editorial policies must evolve quickly to keep up with technology.

From an ethical standpoint, the danger lies not just in errors but also in erasure. Overusing AI tools can sand off the idiosyncrasies of a writer’s style, leading to homogenized prose. Editors must guard against this, ensuring that efficiency does not come at the cost of authenticity.

The Editor as Curator and Cultural Steward

Editors are not just technicians; they are stewards of culture. They shape the voices that enter the public sphere, determine which narratives gain visibility, and uphold the standards of literary and scholarly excellence. These responsibilities cannot be outsourced to algorithms.

AI can support this mission, but it cannot define it. Editors must continue to lead the conversation about language, truth, and expression. They must use AI tools not as replacements, but as extensions—augmenting their insight, amplifying their intuition, and reinforcing their role as cultural curators.

Conclusion

The question isn’t simply, “Will AI replace human editors?” It’s too reductive. The real question is: “How will the role of editors change in an AI-assisted publishing landscape?”

Editors will continue to be indispensable, not in spite of AI, but because of it. As automation handles the mechanical aspects of editing, human editors will be free to do what only humans can—engage with meaning, exercise judgment, and connect with readers on a human level. Their roles will shift, their skills will expand, and their value will deepen.

The future of editing is not a binary choice between human and machine. It is a partnership—uneasy at times but potentially transformative. Editors who embrace this future with open eyes and sharp minds will not only survive but thrive. Publishing, as an industry rooted in both tradition and innovation, will be better for it.

3 thoughts on “Will AI Replace Human Editors?”