Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Early Writing Systems and Materials

- 1. The Invention of the Printing Press

- 2. Industrialization and Mechanized Printing

- 3. The Rise of Photographic and Offset Printing

- 4. Typewriters and Word Processing

- 5. Desktop Publishing and the Digital Revolution

- 6. The Internet and Online Publishing

- 7. E-books and Digital Reading Platforms

- 8. Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Publishing

- Conclusion

Introduction

Publishing has always been about more than just putting words on a page. At its heart, publishing is the transmission of knowledge, stories, and ideas from one person to many. While the essence of this mission has remained constant, the means of achieving it have evolved drastically over time. From chiseling words into stone to encoding them in digital formats, the tools we use to publish have shaped not only how we share information, but also who gets to share it and how widely it travels.

This write-up identifies and discusses important technologies in the history of publishing. Each technological milestone—whether a tool, process, or platform—opens up new possibilities, often democratizing access to information and reshaping cultural and political landscapes. By tracing these innovations, we can better understand how the publishing industry has transformed and where it might be headed next.

Early Writing Systems and Materials

Long before the concept of publishing existed, early human civilizations developed systems of writing as a way to preserve knowledge. The Sumerians created cuneiform on clay tablets around 3400 BCE, a method that allowed them to record trade, laws, and stories. Soon after, ancient Egyptians used papyrus scrolls—pressed and dried strips of the papyrus plant—to record administrative texts, religious writings, and literary works.

These early materials were fragile and labor-intensive to produce. Writing was restricted to a privileged class of scribes and scholars. The creation of texts was slow and limited in scale, making information dissemination an elite activity. Still, these rudimentary methods laid the foundation for more advanced technologies to come.

Eventually, other civilizations introduced their own writing surfaces, such as parchment made from animal skins. Parchment proved to be more durable than papyrus and supported the gradual transition to the codex format—a precursor to the modern book. These developments, though incremental, marked a shift toward portability and preservation, vital traits for future publishing.

1. The Invention of the Printing Press

No single invention has impacted the publishing industry as profoundly as the printing press. Introduced by Johannes Gutenberg in the mid-15th century, the mechanical movable-type printing press enabled the mass production of books for the first time in history. Before Gutenberg, books were hand-copied by scribes, a painstaking process that could take months or even years per manuscript. Gutenberg’s press transformed this laborious craft into an efficient, scalable operation.

Using a combination of movable metal type, oil-based ink, and a screw press (adapted from wine-making technology), Gutenberg’s device allowed pages to be printed quickly and in large quantities. His famous 42-line Bible, completed around 1455, demonstrated the press’s ability to produce high-quality, consistent texts. The press catalyzed a cultural explosion known as the Printing Revolution.

Within decades, printing presses spread across Europe. The cost of books plummeted, literacy rates began to rise, and knowledge became more accessible. The Protestant Reformation, scientific advancements, and political revolutions were all fueled by the press’s capacity to circulate radical ideas. In many ways, Gutenberg’s press was the original information disruptor.

2. Industrialization and Mechanized Printing

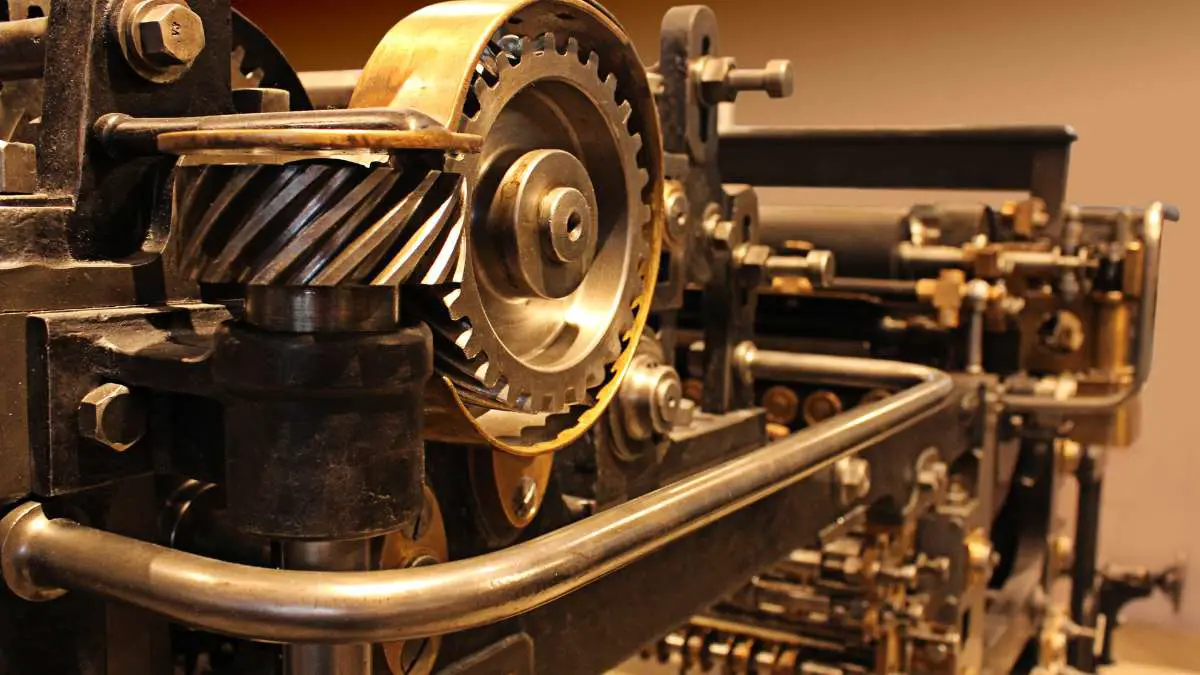

The 19th century brought the Industrial Revolution—and with it, a new era in publishing. Steam-powered presses, such as those invented by Friedrich Koenig and Andreas Bauer, dramatically increased printing speed. A single steam press could print thousands of sheets per hour, far outpacing the manual presses of the previous centuries. This made it feasible to produce newspapers, magazines, and books at an unprecedented scale.

The rotary press, introduced by Richard Hoe in the 1840s, took efficiency even further. By printing on continuous rolls of paper, it supported the birth of modern mass media. Publishers were no longer limited to local or elite audiences. Suddenly, information could be distributed to national and even global readers, laying the groundwork for the first media conglomerates.

At the same time, the development of stereotype and electrotype printing techniques allowed for the reuse of printing plates, reducing typesetting labor. Linotype and Monotype machines, introduced later in the century, automated the composition of text by mechanically assembling lines of type. These inventions turned typesetting from an artisanal skill into an industrial process.

Mechanized printing democratized reading. Books became cheaper, newspapers more timely, and periodicals more diverse. It also introduced new genres—serialized fiction, comic strips, and tabloid journalism—that reached wider audiences. Publishing became not just an intellectual endeavor, but also a commercial enterprise.

3. The Rise of Photographic and Offset Printing

By the early 20th century, photographic techniques revolutionized printing once again. Lithography, originally developed in the 18th century, evolved into offset printing—a process where inked images are transferred from a plate to a rubber blanket and then onto paper. Offset printing, which became standard by the mid-20th century, offered high-speed and high-quality image reproduction, making it ideal for magazines, textbooks, and art books.

The combination of halftone screens and photoengraving allowed for detailed grayscale and full-color image reproduction. Suddenly, photography could be integrated into printed media with stunning clarity. This changed not just how things were printed, but also what was considered printable. Visual journalism, graphic design, and advertising flourished under this new capability.

Offset printing remains in use today, especially for large-volume print jobs. Its efficiency and fidelity made it the dominant form of commercial printing for decades. Even with the rise of digital media, offset printing continues to underpin much of the traditional book and magazine industry.

4. Typewriters and Word Processing

The invention of the typewriter in the 19th century also left a lasting mark on publishing. Typewriters standardized document creation, making manuscripts more legible and professionally formatted. This facilitated clearer communication between authors, editors, and printers. Before the typewriter, handwritten manuscripts could be difficult to read and prone to errors in transcription.

Word processing began in the 1960s with early computers like IBM’s MT/ST, took the typewriter concept further by allowing writers to edit, format, and duplicate their work easily. These early systems were expensive and used primarily by corporate or government offices, but they laid the groundwork for desktop publishing.

By the 1980s and 1990s, word processing software such as WordPerfect and Microsoft Word had become essential tools for writers and publishers. Digital editing not only improved workflow but also opened the door to independent publishing. Authors could now produce camera-ready copies of their books without professional typesetters.

This shift empowered more voices to enter the publishing space and changed the dynamic between writer and publisher. It also paved the way for entirely digital publishing pipelines—something we now take for granted.

5. Desktop Publishing and the Digital Revolution

The 1980s saw another pivotal shift with the advent of desktop publishing (DTP). Enabled by the Apple Macintosh, Adobe PostScript, and software like Aldus PageMaker, DTP allowed individuals to design and typeset their own publications using a personal computer. For the first time, small publishers, nonprofits, and even hobbyists could produce materials that looked professionally made.

Desktop publishing became a game-changer in academic publishing, corporate communications, and independent media. It eliminated the need for large production teams and expensive typesetting equipment. The design process became visual and intuitive, enabling creativity and experimentation.

At the same time, digital file formats such as PDF (Portable Document Format) ensured that layouts and fonts would display consistently across different devices and printers. This was crucial for both print and early e-books. By the late 1990s, digital workflows had become the norm in most publishing houses.

The implications were profound. Publishing timelines shortened, costs dropped, and design capabilities expanded. But more importantly, DTP democratized publishing in a way Gutenberg never could have imagined.

6. The Internet and Online Publishing

The rise of the internet in the 1990s and 2000s completely restructured the publishing ecosystem. Online platforms allowed for instant global distribution at virtually zero marginal cost. Anyone with an internet connection could be a publisher—bloggers, zine creators, citizen journalists, and independent authors all flourished in this new environment.

Early websites and forums provided raw publishing capability, but the introduction of content management systems (CMS) like WordPress and Blogger made it much easier to create and maintain a web presence. These platforms gave users templates, plugins, and design tools to craft professional-looking sites without needing to code.

Online publishing expanded the definition of content itself. Text became just one form of communication, joined by video, audio, infographics, and interactive media. At the same time, digital advertising and SEO introduced new revenue models and content strategies, blurring the lines between editorial and commercial publishing.

While this shift created challenges for traditional media, it also unlocked unprecedented reach. Independent authors could bypass traditional gatekeepers and go directly to readers through newsletters, social media, and websites.

7. E-books and Digital Reading Platforms

E-books emerged as a significant force in the early 2000s, thanks to advancements in e-ink technology and the launch of dedicated reading devices like the Amazon Kindle and Sony Reader. These devices offered the convenience of carrying thousands of books in a single gadget, with adjustable font sizes and long battery life.

Digital distribution platforms transformed how books were sold and read. Amazon, Apple Books, Google Play Books, and Kobo created entire ecosystems where readers could purchase, download, and sync their reading materials across devices. Libraries adopted e-book lending, and educational publishers began producing interactive digital textbooks.

The e-book format lowered barriers to entry for authors and publishers alike. Self-publishing became viable and profitable, leading to an explosion of content in every genre imaginable. It also enabled new forms of storytelling—interactive fiction, multimedia-enhanced books, and serialized digital content.

While e-books haven’t fully replaced printed books, they have secured a permanent place in the publishing landscape. For many readers, the convenience and accessibility of digital reading are hard to beat.

8. Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Publishing

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has begun to shape the publishing industry in ways that were previously in the realm of science fiction. From grammar-checking tools like Grammarly to generative AI systems capable of writing entire articles, AI is becoming a collaborator in the creative process.

AI-driven translation tools are helping publishers reach global audiences without hiring teams of translators. Automated indexing, metadata tagging, and even cover design can now be handled, at least in part, by machine learning algorithms. These tools speed up production and reduce costs, particularly for small publishers with limited staff.

More controversially, AI-generated content is raising questions about authorship, authenticity, and intellectual property. Some publishers have embraced AI to produce content quickly and cheaply, while others remain wary of the ethical implications. Nevertheless, the integration of AI seems inevitable and may redefine editorial standards and publishing norms.

AI is not here to replace human creativity, but rather to augment it. Used wisely, it offers powerful tools to streamline workflows, personalize content, and explore new forms of storytelling. The technology is still evolving, but its potential impact on publishing is enormous.

Conclusion

The history of publishing is the story of technological innovation meeting human imagination. Each advancement—from clay tablets to cloud computing—has expanded our capacity to share knowledge, connect communities, and preserve culture. These technologies have not only changed how content is produced and distributed but also influenced what gets published and who gets to publish it.

Today, publishing sits at the crossroads of tradition and transformation. While print still holds cultural and aesthetic value, digital technologies continue to reshape every aspect of the industry. And with AI on the horizon, we’re likely just at the beginning of yet another profound shift.

Understanding the technologies that shaped publishing helps us make sense of where it’s going. It reminds us that publishing is not just a business or a process—it’s a living, evolving dialogue between people and ideas, powered by the tools they create.